“What is Weight-Inclusive Cognitive Behavioral Therapy CBT-WI?

Cognitive-Behavioral Therapy is the most effective approach for treating adults with eating disorders, including bulimia nervosa and binge eating disorder. The most recent, commonly taught, and implemented version is an “enhanced” protocol, CBT-E (Fairburn, Christopher G., 2008). Unfortunately, Cognitive Behavioral Therapy (CBT) for eating disorders is not always employed in a weight-neutral way. It includes language and practices that can be uncomfortable, stigmatizing, and in some cases, harmful to individuals in larger bodies who are seeking treatment for an eating disorder. As such, I have adapted it to be delivered in a manner that is consistent with a Health at Every Size® approach.

I am often asked how I employ CBT-E in a HAES-aligned way. Having trained in CBT for eating disorders (under Terry Wilson, Ph.D., back before it was known as CBT-E) and having developed a strong HAES stance over the past 10 years, I have always known CBT as an anti-diet model. I think the earliest manual in which I was trained (a typewritten manuscript from 1991 that predated the first published version in 1993)—which was really quite sparse—had less weight stigma than the most recent version. In a recent review of the most updated manual, the encroachment of weight bias is evident, especially through my staunchly HAES® -aligned, fat-positive lens.

![CBT plus HAES for Eating Disorders in Los Angeles, California | 95965 | 92270 | 92241 | 93552 CBT plus HAES for Eating Disorders [Image description: large bodied gender neutral person seated and facing a therapist whose back is to the camera] represents a potential client with an eating disorder receiving CBT plus HAES in Los Angeles, California](https://www.eatingdisordertherapyla.com/wp-content/uploads/2023/01/allgo-an-app-for-plus-size-people-OxwQT1woe-Y-unsplash-300x200.jpg)

CBT for Eating Disorders

There is a clear history behind this development: the manual was, after all, written in the 1990s by two thin white men who made assumptions about bodies based on that era’s prevailing health paradigm. A content analysis of the various manuals (Fairburn, 2008 and Waller et al., 2007) reveals a great deal of weight bias and assumptions about body size. For example, Fairburn (2008) writes that for patients who are “obese”, “the other option is to treat the eating disorder first, the goal being to give patients control over their eating, and then they can consider tackling their weight” (p. 253).

Fairburn also writes, “binge eating apart, overeating is not common among patients with eating disorders, the exception being those with binge eating disorder… they have a general tendency to overeat” (pp. 14-15). Waller and colleagues write “Once the eating disorder is less of a pressing issue and food intake is more stable, the focus can then turn to weight loss” and goes on to state “we advise clinicians to take a step back and see the resolution of the eating disorder as the first step in the long process of weight management.” (Waller et al. 2007, p. 88).

Anti-Diet But With Contradictions

At the heart of the model, CBT is anti-diet. The main focus at the outset of treatment is on eliminating dietary restriction and working towards flexible eating and the incorporation of all—including previously feared/forbidden—foods. I believe this core concept allows CBT to be applicable to people in all bodies.

Despite this focus on adequate and inclusive eating as the primary means of eliminating binge eating and/or purging, the manual presents contradictions about the restriction of food intake. For instance, the CBT-E manual recommends that after bingeing is brought under control, people in larger bodies could be educated about “healthy ways to lose weight,” including “binge-proof dieting” (Fairburn, p. 255). I believe this is wildly problematic, as dieting in any shape or form is risky for anyone with an eating disorder history. I never promote the pursuit of weight loss.

Previously, I spoke and wrote (and even presented to Terry Wilson) about changes that need to be made to the manual to ensure that it can be employed in a weight-inclusive way. I will share the major modifications I make here. (Terry Wilson verbally encouraged me to modify the manual.)

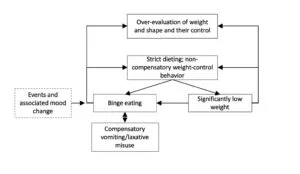

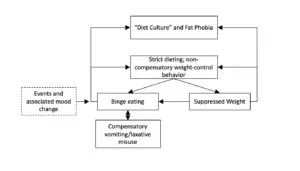

CBT Cognitive Model Adapted for CBT-WI

First, I have modified the cognitive model itself. Whereas Fairburn posits that low self-esteem—in turn leading to an “overconcern with shape and weight”—is the primary driver of dietary restriction, I have replaced this with “diet culture” or, even more aptly, “anti-fat bias,” which locates the problem outside the individual and in our toxic society. This correctly redefines the situation: it is not a pathology of the individual, but an understandable reaction to their body’s lack of conformity to society’s most coveted size, or to the potential loss of “thin privilege”.

My second modification to the model is to replace “low weight” with “suppressed weight.” This recognizes the common presentation of atypical anorexia and more aptly reflects research studies describing the impact of weight suppression on symptom maintenance in bulimia nervosa.

Self-Monitoring in CBT-WI

Self-monitoring of food intake is a key feature of CBT for eating disorders. Individuals who have participated in “weight management” interventions often express fear about keeping food logs. For patients with this history, it is often helpful to explore previous experiences with self-monitoring and how this practice is different.

Focus on Weight in CBT-WI

The manual encourages practitioners to let people know they are unlikely to gain weight with this treatment if they are in the “healthy weight range.” This reassurance is blatantly fatphobic; it implicitly reinforces the idea that being fat is something to be feared, and it is probably incorrect based on the existence of atypical anorexia as well as recent evidence that weight suppression maintains bulimic symptoms. It is far better, in my opinion, to let people know that we do not know what size their bodies will ultimately be when recovered. If they are weight suppressed, I think it is good informed consent to let them know they will likely need to gain weight to fully recover.

In CBT-WI, we should eliminate any focus on knowing one’s weight at the beginning of treatment, weekly weighing, and BMI range. I do not do mandatory weekly weighing unless someone is restoring weight (in which case, I’m likely not doing CBT-E). I think collaborative weighing has its place, such as when weaning a person from weighing themselves too frequently or in cases where a person is intentionally working on learning to accept their weight. However, we live in a culture where being higher weight is vilified and seen as a moral failing. Thus, for many higher-weight clients, weight is not a neutral stimulus to which they can be simply desensitized. Weekly in-session weighing has the potential to reinforce the focus on weight and away from symptom improvement, affect eating behavior between sessions, and be anxiety-provoking enough to discourage treatment attendance altogether.

Regular Eating in CBT-WI

![CBT plus HAES in Los Angeles, California | 94040 | 96003 | 90274 | 95965 CBT Plus HAES [Image description: Purple scrabble tiles spelling "CBT plus HAES"] representing the eating disorder counseling provided at EDTLA in Los Angeles, California](https://www.eatingdisordertherapyla.com/wp-content/uploads/2023/01/IMG_2725-300x225.jpg)

After introducing regular eating, I introduce appetite awareness training (Craighead, 2006). This is another CBT manual that offers an appetite rating tool to help clients rate their hunger before and after each episode of eating based on a scale of 1 to 7 to help determine whether meals are adequately satiating. This helps the person avoid extreme hunger that may set up a binge. I also work to depathologize eating past fullness and I introduce self-compassion for those times when people do eat past fullness.

Psychoeducation About Basic Needs and Regular Eating

I educate clients about the five basic needs—food, water, air, warmth, and sleep—and normalize the reality that our bodies prioritize the attainment of any unmet need. In addition, I explain that the body is wise to drive eating behavior in the face of restriction or undereating. I let clients know that I can’t help them override their hunger drive and that my skills and strategies won’t work if they are not eating enough for their bodies.

I also work to normalize eating when not hungry to maintain structured eating. Only after eating has become regular—3 meals and 2 to 3 snacks per day—and hunger-fullness is staying in the middle range, can we address breakthrough binges with the addition of other coping skills. I work to normalize soothing with food. I believe that “emotional eating” is typical and only a problem if it is the client’s only coping skill.

CBT Body Image Interventions in CBT-WI

Body image interventions in traditional CBT can also be problematic. Body exposure activities that instruct a patient to face or “expose” their body by wearing more form-fitting or revealing clothing in public or visiting certain places such as gyms fail to properly prepare patients in larger bodies for the potential for weight discrimination. We must carefully explore the potential for an invalidating environment before assigning exposures. Activities that focus on proving to a person that their body image is distorted—and hence, they are “not as fat” as they believe—are also inherently fatphobic. Oftentimes, clients seeking treatment for an eating disorder are living in or recovering into larger fat bodies. I have effectively eliminated any body image distortion interventions that try to reassure someone that their body size estimations are wrong—these are fatphobic.

The CBT-E body image interventions I incorporate include awareness of body checking and body avoidance. We work towards moderation of each—limiting checking and decreasing avoidance. I provide education on the harmful effects of extreme body-checking behaviors such as measuring, pinching, or frequent use of photos to eliminate these behaviors. We address body avoidance by exploring normative mirror use and supporting clients in pursuing social or movement activities in their bodies as they are now. Appropriately being in photos also addresses body avoidance.

“Feeling Fat” in CBT-WI

The module on “feeling fat” also needs modification. In Fairburn’s manual, he instructs patients to monitor feelings of “fatness.” However, fat is a body size and not a feeling. This exercise conflates fatness with negative and bad feelings like disgust and self-hatred. A potential reframe would be asking clients to identify “momentary extreme body discomfort/dissatisfaction episodes.” These might be either physical sensations or mood states, almost like a body image panic attack. It can be helpful to educate clients that we have these mindset shifts in and about our bodies that can be very real but don’t require eating disorder behaviors to manage. We can help them see that such episodes might pass independently. Or perhaps they can manage them by changing into more comfortable clothing, for example.

Feelings of “fatness” are a commonly reported experience among individuals with eating disorders—and are even assessed for directly in standardized eating disorder symptom inventories. However, we can also help our clients of all body sizes to reframe this negative feeling to what it really reflects, which may be feeling unworthy, unloveable, inadequate, etc. We can help them develop language for these feelings and reduce rather than reinforce negative associations with fatness. At the same time, we can also help bigger clients to reclaim the word “fat” as a neutral term.

Behavioral Experiments in CBT-WI

Many behavioral experiments test whether eating something causes as much weight gain as the person predicts. Unfortunately, this experimental design reinforces one core idea—that gaining weight would be a negative consequence—rather than dismantling it. It is better to conduct experiments that challenge other outcomes that patients believe will happen if they eat regular meals or gain weight— e.g.. “I won’t be able to handle it”, “I’ll hate myself”, or “I’ll feel anxious.” We can design experiments to demonstrate that they can tolerate whatever happens. Instead of measuring weight changes, clients can measure distress, guilt and shame, preoccupation with food and body, or how much time one spends engaging with their eating disorder.

Addition of HAES Advocacy

I provide education about weight stigma and oppression. Also, I validate that body distress is a normal response to the cultural message we receive. Finally, I provide strategies aimed to manage body distress that take into account that a person’s lived experience may be one in which they’ve experienced stigma.

Coming Soon: The Weight-Inclusive CBT Workbook for Eating Disorders: (available 2026)Tools to Reject Diet Culture, Heal Body Shame, and Promote Recovery

Book by Our Practice Owner, Lauren Muhlheim, Psy.D. and co-authors Jennifer Averyt PhD ABPP (Author), Shannon Patterson MEd PhD (Author), Carolyn Black Becker PhD (Foreword).

I want to give special thanks to Rachel Millner, Ph. D., Shannon Patterson, Ph. D., and Elisha Carcieri, Ph. D., who have been instrumental in helping me develop these modifications.

I can provide trainings for professionals on integrating weight neutrality into CBT and other evidence-based treatments.

Sources

Fairburn, C. G. (2008). Cognitive behavior therapy and eating disorders. Guilford Press.

Fairburn, C. G., Marcus, M. D., & Wilson, G. T. (1993). Cognitive-behavioral therapy for binge eating and bulimia nervosa: A comprehensive treatment manual. In C. G. Fairburn & G. T. Wilson (Eds.), Binge eating: Nature, assessment, and treatment (p. 361–404). Guilford Press.

Millner, R. and Muhlheim, L. (2021) Anti-fat bias in evidence-based psychotherapies for eating disorders book. Can they be adapted to address the harm? In Weight Bias in Health Education: Routledge

Waller, G., Cordery, H., Corstorphine, E., Hinrichsen, H., Lawson, R., Mountford, V., & Russell, K. (2007). Cognitive behavioral therapy for eating disorders: A comprehensive treatment guide. Cambridge University Press.